Net-positive development explained

The Greenbelt faces pressure and stress from development and expansion of the ‘Golden Horseshoe’ as the population increases.

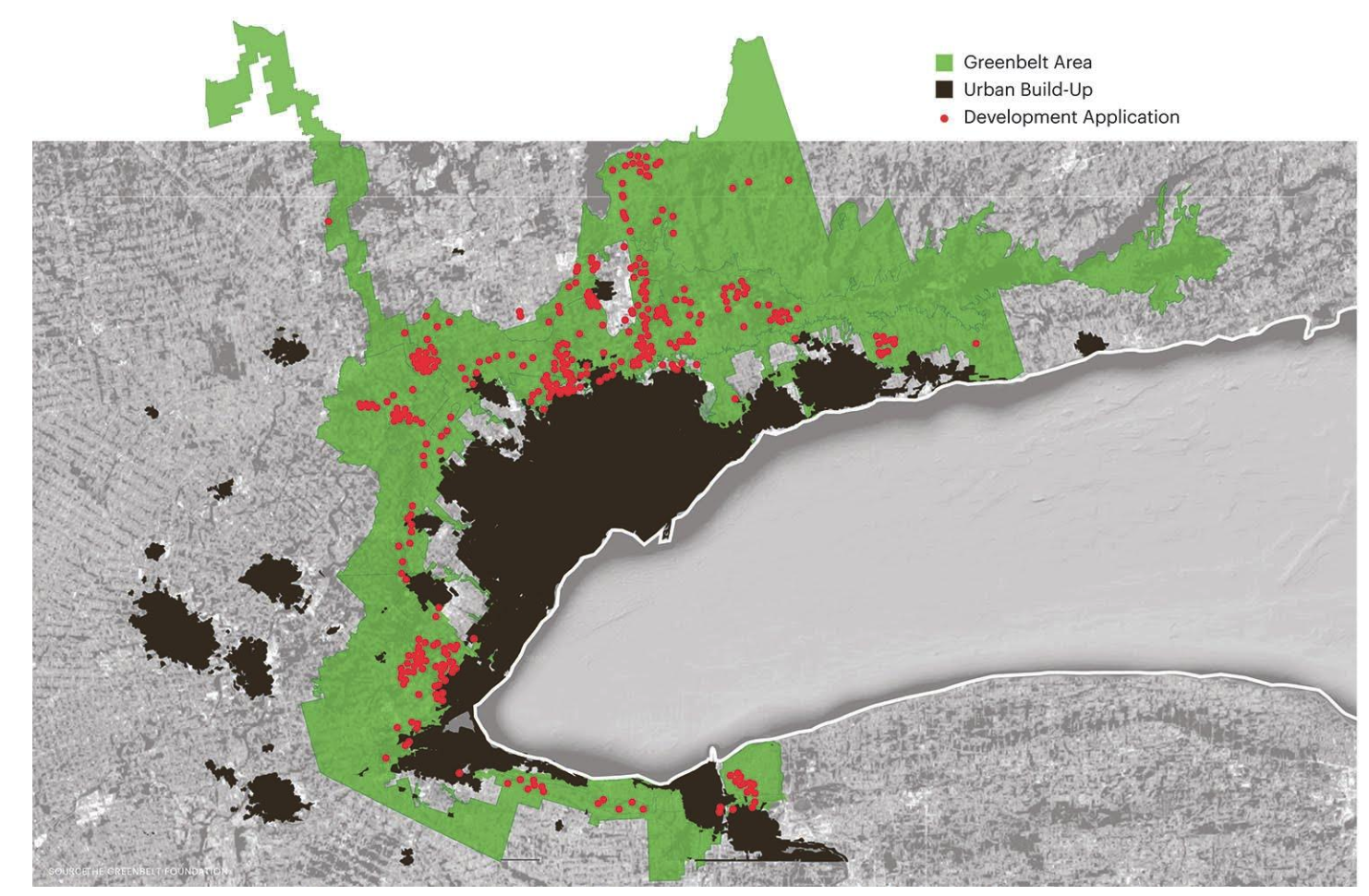

As seen in the provided map, nearly 600 development applications were made within the Greenbelt in 2014 alone 6. Development in the Greenbelt seems inevitable.

Sustainable would be remiss to not aim to shift the current perceptions that all building and development is ‘bad’ and start exploring architecture as a method of creating net-positive development which is of benefit to the immediately-surrounding environment.

Inexorable Encroachment

This project demonstrates methods for developing architecture with better building envelopes and smart planning such that it can have a positive impact on

natural ecosystems. Change must happen at all scales, from national infrastructure projects to regional planning policies to local land use and wastewater management.

It is no longer enough to simply slow down emissions – we must to stop the trend by challenging entrenched modes of planning and building in order to turn things around and create positive change.

Ontario’s Greenbelt provides invaluable natural capital to the province. It has more than 2 million acres of land, compared to the entirety of Prince Edward Island at 1.4 million acres.

It protects the farmland that we need to sustain our way of life, and it keeps safe the forests and wetlands (10,000 km of trails, and protection of water supplies) that provide immeasurable benefit to the wellbeing of the region.

The Greenbelt acts as a natural water filtration system for the entire region 7.

In order to efficiently protect this legacy, we must elevate ecology in the strategies for development adjacent to the Greenbelt.

Frequently, politicians or lobbyists will float the idea of opening the Greenbelt to development, potentially slashing protections and regulations to enable clear-cutting of invaluable land to support ever-growing suburban sprawl around the Greater Toronto Area.

There is an often-cited need for more housing stock in the region and the only apparent solution is to ‘regrettably’ cannibalize these protected lands. While these arguments are flimsy at best (studies have shown that projected growth can be accommodated within already earmarked land 9) they demonstrate the relentlessness of developers to encroach on the Greenbelt.

This project aims to provide an alternative to traditional methods and to prove that it is possible for development to provide a net gain for their surrounding environments.

Alternative Development Strategies

Right now, there is a demand for single-family homes driven by population growth in the GTA. Sprawl has little regard for context and generally has poor integration with nature – often involving the destruction of valuable land and ecosystems.

The dream of material wealth in a large home, big lots and multiple cars is unsustainable across the board, as it is unaffordable to the majority of the population and leads to massive environmental degradation. It is estimated that there is enough desirable land in the GTA to accommodate projected growth for the next few decades. The question becomes: what will happen after that?

Sustainable proposes to harmonize the seemingly inevitable greenfield development with site ecology through a case-study project North of Toronto.

This project improves a development application originally approved in the 1990s and grandfathered-in after the Greenbelt protection laws came into effect. The original application consisted of 33 estate-lot homes at 3600 sq. ft. each with half acre lots and a clear-cut forest to accommodate extensive septic tile beds. This represents the standard method of development but the owner now wants to set the bar higher - aiming to do less harm to the environment. Sustainable proposes to go further, and to create a development that will actively help the environment.

To begin, ecologists and arborists were brought in to assess the site. It was identified that a large portion of the site was once cleared with intent to create monoculture plantations - in other words: it is not entirely a virgin native forest. At some point scotch pine was planted and while it has been naturalized, it is still an invasive species and is thus vulnerable to disease and stunting the growth of local species. This provides a location for our development.

By concentrating development on areas that already require remediation, the more sensitive areas of the site are better able to remain healthy and are encouraged to once again thrive, surrounding the residential development with healthy ecology rather than a clear-cut steamrolled subdivision.

The ‘Better Way’

With a sense of how the site planning should take shape, we looked at the requirements of a residential development through the lens of ecologically-sound design. The original application was for a development of ‘McMansion’ type residences. We propose the idea of simplified building volumes with compact footprints that still contain the essential elements of the home as originally proposed inside an efficient and optimally-oriented enclosure.

A mixture of housing types is provided ranging from bungalows to semi-detached homes and townhouses, representing the ‘missing middle’ housing typologies in Ontario. Overall the developed land area is reduced, while providing more housing units of more types than originally proposed.

The site is located within easy travel distance to public transportation amenities such as the GO regional transit line. Personal transportation access is considered across the site in conjunction with underground services: permeable paving with drainage swales that filter water naturally on-site rather than pumping to a treatment plant off-site.

Constructed wetlands are used to treat waste water on-site using single household treatment systems located throughout the development to take advantage of natural gravity flows. In addition to water treatment, these wetlands provide protection from flooding and will become habitats for various wildlife. Grey-water re-use systems are proposed as well as mechanisms to collect and use storm water. In addition to the on-site aquifer, these interventions could reduce a Markham resident’s average water use from a 189L per person per day to an estimated 56L 10.

Various renewable energy systems are proposed, including communal battery systems and geo-exchange loops to use low-grade heat to its highest potential. Photovoltaic panels installed on optimally-oriented roof planes harvest solar energy while reflective roofing materials and high thermal mass enable effective passive solar strategies to be employed.

Houses are designed at Passive House Standard 2300 kWh per year which is 25% of the baseline Ontario Building Code house at 9000 kWh per year 11.

The dwellings are a model of passive building strategies, beginning with a well-insulated and air-sealed enclosure and incorporating optimized site orientation to passively take advantage of nature’s energy are better able to remain healthy and are encouraged to once again thrive, surrounding the residential development with healthy ecology rather than a clear-cut steamrolled subdivision.

Bungalow Home Design

Integrated Systems

One of our goals with this project is to create spaces for community development, and to provide opportunities for residents to learn more about sustainable ways of life.

As such, a cornerstone of the development is the Sustainable Living Centre. This Centre addresses site and county-wide education and community programs, and provides facilities to support forest management. It serves as an educational tool and a base for recreational activities through rehabilitated forest areas. Integrated plans for forest rehabilitation will also ensure milled timber from the invasive species mitigation become a source for local construction and export to the wider market. The success of the neighbourhood can be measured through community interaction, investment, learning opportunities and participation.

The Sustainable Living Centre also acts as a community hub hosting public events, community gatherings, and farmers markets. Domestic farming infrastructure was placed in areas cleared for solar exposure to houses. Local crops such as asparagus, broccoli, cucumber and peppers and squash can be grown in these plots, while microgreens are grown indoors year-round. Extra crop yields can be sold to residents and visitors at the local farmers market.

Sustainable Development

This project is an exercise in realistic problem-solving. Development in the sensitive areas of the Greenbelt seems inexorable, and the policy framework we would need to combat this movement is out of the hands of architects.

Through the design of this neighbourhood, we present an alternative to the traditional methods of suburban development by changing our perspective to view opportunities instead of problems.

By taking a considerate, site-specific, ecological approach to master-planning and by incorporating and integrating multiple levels of sustainable strategies we have enabled the creation of a vibrant, self-sustaining community which has a positive environmental impact on the surrounding region.

Sources:

6 Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation, Maps, http://www.greenbelt.ca/maps.

9 Jeff Gray, Is the greenbelt squeezing Toronto’s housing market?, Globe and Mail, (Toronto, 2018), https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/toronto/is-the-greenbelt-squeezing-torontos-housingmarket/article32369107/

10 The Official Site of the City of Markham, Water and Sewer, https://www.markham.ca/wps/portal/home/neighbourhood-services/water-sewer/how-to-use-less-water/05-how-to-use-less-water

11 Passivehouse Canada, About Passive House, https://www.passivehousecanada.com/about-passive-house/.